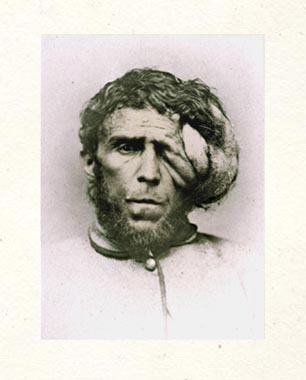

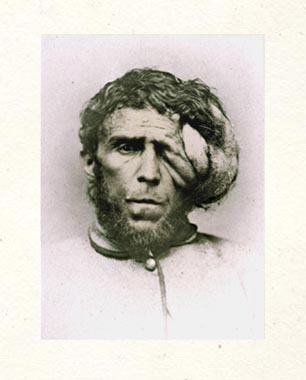

THE PENDULOUS GROWTHS upon the right side of this patient's head, and a number of small and soft tumors on various parts of the body, were congenital. During childhood, and even until thirty years of age, the tumor of the scalp steadily increased in size, from year to year. Since coming to this country, sixteen years ago, patient thinks there has been no permanent change. Patient suffers more inconvenience from the weight of the tumor in summer than in winter. When exposed to a low temperature in winter, the lax tissue becomes icy cold, but have never been at all benumbed. About five years ago, while at work, a shovelful of gravel was accidentally thrown against the right side of his head, on account of which accident he entered Bellevue Hospital, April 1874. The growth was injured, several slight wounds continued to discharge, and an attack of erysipelas (St. Anthony's fire) supervened. Since then he has been employed in hospital and has suffered again from erysipelas, to which affection he seems unusually prone. The treatment of fibroma is not imperative, as the affection occasions no discomfort.

After Papa saw him, he said, "You think

I'm gonna let you marry that! My God,

he's a freak; you want your kids to look like him?

You'd mark them lookin' at that nine months.

It'd turn your baby's head to a mess like his."

"But if you only look at half his face,

I said, "it don't look bad at all."

You can guess the things that didn't happen

in their lives—or wish them generous biographies

they could never have known, perfect

and plummet-measured in chiseled proportions.

The facts, however, are these:

the objects he would never have:

drawers filled with linens and small bags

of cedar shavings, aprons on kitchen nails,

rolling pins, boxes of Mason jars, tops

and string: and all the bile that she

would wash upon the life she got,

her father's, husband's—perhaps her son's.

But does such guessing chronicle a true history?

Can fact be in what would not be,

or data discerned in silver salts

and visage alone? Little more, I'd guess,

than truth in the random dictates

of our naked flesh. What then does the eye

but the lures of attraction,

the centuries of swollen sentiment,

the mudden layers and all their wiggling fossils

of culture and prejudice see?

Consider what she said,

and with your hand

or a bit of paper

bisect his face,

cover the growth,

imagine you never saw it.

Then consider who you see.

Could this not be—and be as true—

were we again making histories

and crystaling with conjecture a face,

Michael Knightly,

Victorian essayist, Carlyle's friend and rival,

whose Fumus Fugiens is still read to remind

our vanity how close sits the skull,

how grand grows the worm;

or Matthew King,

American poet, who with Whitman

shaped our visions and voices,

whose "Brown Pindarics" would not elegize

but stood him only at the gallows

but like youthful Aristokleidas:

O Columbia! It is your blood in him.

He merits songs' jubilation,

and so I send him honey,

white milk, the music of forest flutes.

Live now, John Brown,

superior and in glory,

forever in Kleo's grace; or even yet,

Maurice-Gustave Kahn,

the "Enigmatic Impressionist"—

and in his famed smock, as well!

CÚzanne's dearest friend,

whose money helped them all,

who said of art, "It's dilemma

and delusion. I paint impressions,

guesses—nothing the eye can see."

So what do all these fictions of a small fact,

a few fading inches by a few fading inches,

mean? It is a false validity alone

George Fox's words and my lines give to the first.

Can I be so certain where fibroma took him

or into what cedared and richly scented,

what top-spinning warmth, he was already accustomed?

Kahn said, Forget truth. And Knightly said,

Reality is as shifting as smoke in a dream. King said,

Whatever the heart reads is real. Michael Keane

looked out with his single eye and said,

It could have been a different life.