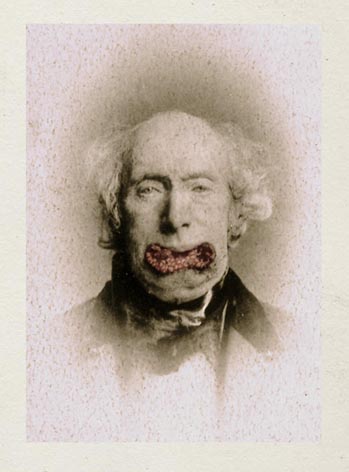

THIS PATIENT had always been a strong, healthy, hard-working man before the development of the epithelioma, and had worked generally with a pipe in his mouth. Two and a half years before the picture was taken, a small lump began to be felt on the left side of the lower lip. This became hard, superficially eroded, and covered with a scab. Gradually the growth invaded the greater portion of the lip, although it was over two years before destructive ulceration began. In the central portion of the lip there had been loss of tissue, and there was such a continual dribbling of saliva that the patient usually kept a handkerchief pressed upon his chin, and in sitting for his photograph it was necessary to put a rubber cloth over his breast to protect his clothing. The treatment of epithelioma usually demands prompt and active measures. The earlier the patch can be destroyed the better. When progress is very rapid, the immediate removal of the diseased part, or its complete destruction by means of a powerful caustic, is the only treatment worthy of being considered. In cases where the disease is not progressive, and especially where the patient objects to the knife or cautery, I would advise arsenic in small and long-continued doses. In the use of caustics failure and even harm often results from an insufficient application of the caustic, through fear of going too deeply, or causing too much pain. The growth, instead of being totally destroyed, merely becomes inflamed, and is stimulated to further increase in extent.

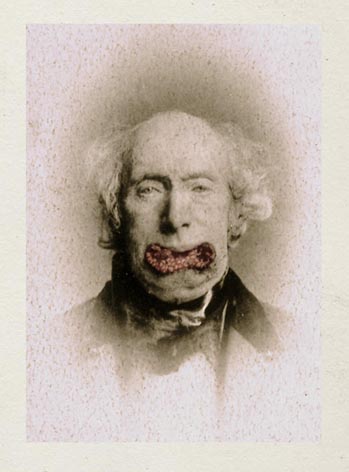

I've asked and asked why God afflicted me.

I'm sure it's not for something I have done

for I've always done as I'd be done by—

perhaps something I neglected to do.

But could it have merited such rebuke?

No blasphemy ever fell from where once

my lips were—only praise and thanksgiving

for my lot. Now I'm reduced to drooling,

and must turn from my wife of fifty years,

whose lips I'd still be kissing had I still lips.

I've sometimes thought I am some modern Job

being tested, but no other tests have come:

my wife and children are all well; my wealth

has not diminished; boils have not appeared;

and I'm not even taunted by street boys:

they doff their caps, say "Morning, Sir," as if

nothing had changed at all. Quite clearly then

I am no Job, but I'm left more perplexed,

left without irony's odd benefit,

for I'm no blind poet—no mute preacher

whose justifying iambics, whose prayers

set to do wonders, went undelivered.

I am an ordinary husband, father,

businessman, never stole from anyone

and had so many friends—note the past tense.

Is there any meaning to this at all?

Perhaps it's in how I carry the pain.

I know that better men have suffered worse,

but that's a fact that little comforts me.

All suffering is singular. My pain

is not assuaged by pains which outreach mine,

and I find nothing in a neighbor's plight,

regardless how much worse it is than mine,

to take some sickening solace in. Of course

I'm glad I am not he, but just as glad

not to be some younger, unafflicted,

richer anyone, for he would not be

me, who's husband to an old wife, father

to children whose memory in my life

is worth more to me than my whole life's worth.

I most fear there's no meaning here at all,

no more than if I'd stumbled on a rock

and tripped: rock and stumble and trip: that's all.

But can caprice so drive our happiness,

shape our disgusts and failures, be the lures

that catch and pulley us, but not perhaps

to God but toward the alien banks, there

where all sense of stream collapses in air

that takes our breath away and leaves our eyes

shocked and milky, blinking at a world turned

too clear for previous vision. The brain

then reels, bolts, and goes out in brilliant, deep,

shimmering disasters of air and light.

Thoughts like these erode the heart. Don't listen,

Love; I'm a foolish old man, and these times

are bothersome, and I, occasionally,

melancholy, but Dr. Fox will help.

I'm sure, and think I'm sure we will kiss again—

for surely there must be some meaning here.