From Griffith.

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

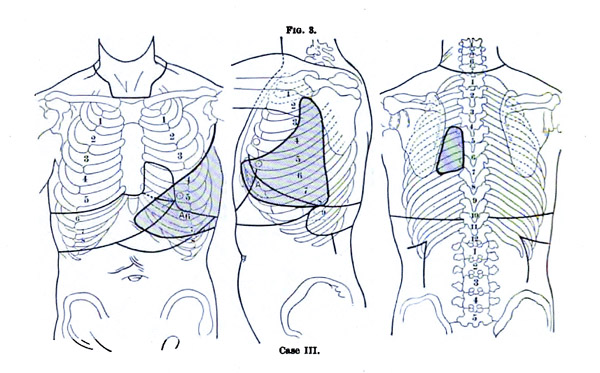

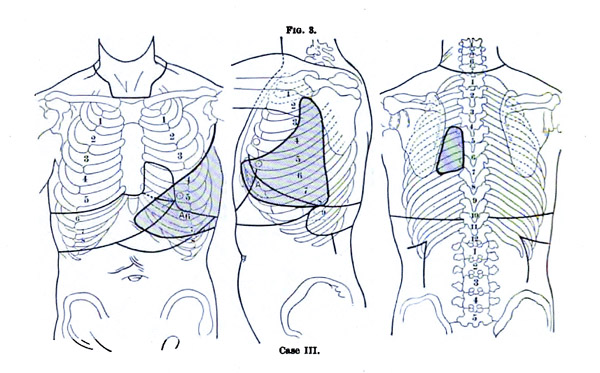

The clinical portrait of Jennie Savage that falls on page 123 of the Mütter was taken on December 15, 1894 when she was only about 9 years old. She was examined for a paper on auscultation by Dr. J. P. Crozer Griffith titled, The area of the murmur of mitral stenosis, which he read before the Association of American Physicians and published in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 38 Griffith's intention was to disabuse his colleagues of the notion that systolic murmur is always confined within the narrow region of the apex beat in cases of mitral stenosis. This fact had already been established in the literature — Griffith provides the sources — but it was forgotten and omitted from the current textbooks. He presented seven cases, each with a diagram showing the wide range of murmur he was able to detect. In three of the cases, including Jennie's, the soundings appeared in back near the scapula:

CASE III. –Jennie S., nine years old. Slightly built and undersized. Previous history and history of other diseases unknown, except that she had been an inmate of the Children's Hospital at different times during the greater part of two years, suffering from very severe cardiac symptoms which often threatened life and at other times were largely quiescent. There had been repeated nose-bleed, intense cardiac pain, congestion of the lungs with fever, great dyspnoea, palpitation, but no or but little oedema. Examinations of the heart were made at various times, all corresponding for the most part in their result. In May, 1894, the examination showed : Bulging praecordium ; wide, heaving impulse; apex-beat best felt in sixth interspace in the nipple-line ; distinct diastolic thrill. Boundaries of the cardiac dulness were the second rib slightly to right of right edge of sternum; fully one inch to left of the left nipple-line. The auscultatory symptoms were much as at the final examination made in March, 1895, at a time when the child was playing about the ward and was in very good condition. The notes of this examination read as follows: At apex, which is in the sixth interspace one inch outside of the nipple-line, there is a loud, roaring murmur occupying all of the diastole, followed by a loud systolic murmur. The latter is transmitted into the axilla. The diastolic murmur is transmitted downward from the apex to the costal margin, thence transversely to the left to the posterior axillary line in the eighth interspace, thence high into the armpit, thence obliquely downward to the nipple in the fifth interspace, thence obliquely to the xiphoid cartilage, and thence finally to the left costal margin. The horizontal breadth of the murmur is five inches, and the height three and a half inches, a very large area in a child no larger than the ordinary size of six or seven years. The maximum intensity is at the apex and in the eighth interspace in the axilla. The murmur is audible between the spinal column and the edge of the left scapula. No murmurs heard at the aortic cartilage or in the neck. Second sound much accentuated at the pulmonary cartilage, and a systolic murmur heard there.

Why did Griffith say a prior history of disease was "unknown?" Were Jennie's parents dead? Was she abandoned?

The Mütter caption for the photograph of Jennie simply gives "enlarged heart," a term that is as imprecise as "hermaphrodite,"

but without a history or anamnesis the best guess that can be made is that her condition was an acquired defect, probably

from rheumatic fever. The paper was not very significant, a small step in the pedagogy of heart disease, but reconnecting Jennie's

photograph with Dr. Griffith's report provides a vivid picture of historical cardiology that now accrues to the

importance of these two documents.

The reconnecting of images to case reports also accrues to contemporary interest in nineteenth century medical photography, particularly among artists who share with physicians a fascination for the endless complexities of the human form. Almost all of the photographs in the Mütter book come from the formative years of medical photography before patient confidentiality and nudity issues emerged to broker its production. These issues entered public discourse for the first time in 1895 by way of a lawsuit brought against Dr. Augustus Charles Bernays (1854-1906) because of a paper he wrote titled, An operation for the relief of impermeable occlusion of the œsophagus of five years' standing, with dilatation by a new method. 39 Bernays illustrated his paper with a photograph of his partially nude six year-old patient, Anita May George, who at the age of two accidently swallowed lye and suffered a stenosis so complete she required a gastrostomy to survive. When Anita came to Dr. Bernays in 1895 her condition was grave, she had the appearance of a dwarf, weighed only 19 pounds, her fistula was leaking and she was probably losing the lining of her stomach. Doctor Bernays was a specialist in gastro-intestinal surgery, and with superb skill and invention he saved his young patient's life by dilating the œsophageal stricture with incremental sizes of a rosary bougie. It was an extraordinarily difficult series of operations which were cited by Warren of Harvard as "among the most daring ever undertaken." However, because Bernays published a photograph of the child, stripped to the waist to show the results of his surgery, the parents were inspired to sue him for soiling her modesty. In her memoir of her brother, Theka Bernays blames the trial and its scandals for bringing Bernays to an early death : 40

When one considers the amount of heroism required by men who thus bear the banner of scientific progress into new territory without counting the fearful cost to their nerves, it is no great wonder their hearts give out at fifty-two. Working amidst suffering, under difficulties, facing danger all the days of the long years, and lying awake many hours of the night devising the steps of tomorrow's cases, or reviewing in memory those of today, wondering whether the fraction of a chance has been missed, the minimum of a possible advantage overlooked, how can they long resist such a strain ? Even while engaged in the struggle to stay the suffering, to prolong the years for their patients, to promote the science they are trying to serve, they are obliged constantly to defend their own character and reputation against the attacks of captious and envious rivals in their own ranks.

Bernays won the case, but thereafter clinical photography followed the trend of medical composition into monotonized anti-narrative structures. Patient identity issues in medical photography comprise one of the subjects of Martin Kemp's chapter of Beauty of another order, 41 in which he wrote the following:

With the exception of special illustrations of pathology, in which a report on a particular case will place an emphasis upon what is specific in this individual instance, there has been a general tendency to nudge the photographic image used for pedagogy in the direction of the normative, through a careful rigging of the various medical, visual and technical choices. — pages 122-123.

The texts that were illustrated photographically frequently aspired to present sober accounts of empirical observations and procedures, in which the personalities of the scientists as emotional and social entities were increasingly excluded — at least from the most direct scrutiny. — page 148.

This trend toward a "rhetoric of reality" — I hope Martin Kemp will forgive my misappropriation of his term — led also to the exclusion of patient identity from medical tracts.

I think we are starting to sense what was lost by abstracting patient identity and narrative from the study of disease. The argument for its reintroduction is an obvious one: that every illness is unique to the individual — to know the cultivar is to know the disease. Leafing through the pages of the Mütter book I am struck by the variety of bodies and how the disorders depicted are wonderments of nature's stranger and more terrible beauty. To be sure, many of these people are beset by tragedy, but did they need the additional misfortune of shame put on them? And doesn't the abstraction of their identities only continue the work of shame? The photograph of Herold Alfont on page 99 of the Mütter is a fantastic image and I would have loved to have known the guy. To me he is saying, "I don't have a condition of epispadias, I have a condition of Herold Alfontspadias and look what I can do!" To borrow another expression from Martin Kemp, there is no "border information" of shame creeping into the image, not for Herold, not for the photographer or examining physician, and not for those of us who cannot stop looking at him.

What most impressed me about Gretchen Worden when she was alive was her profound humanism. As the director of the Mütter she had to manage the needs of physicians, artists, and all manner of the uninformed, prurient, horrified, disturbed and uncertain. She pitched a big tent and no one was turned away. It took me a while to get over my prima facie criticism of the Mütter book for some of the images that were chosen, but then I remembered what Gretchen was all about and what she wanted in return for our tickets. The same generosity of spirit giving as given. The Wendt photograph on page 79 is not what I would have chosen for an example of morbid obesity, but maybe someone else will be moved by the photograph to learn a little more about the condition and be less critical if not appreciative of nature's beauty when it is encountered on the streets of Philadelphia.

However, a methodology for weighing these images might bring a little order to the tent and it might not be unreasonable to use a scale, lets call it the Gretchen Worden differential scale of 1 to 10, that is asymptotic at its ends. The Gretchen scale would adjust for the aesthetic concerns of an image along with the gravitas of its medical science content. An example of a close ten could be the Niobe plate from Duchenne's "aesthetics" or one of Dr. Hugh Welch Diamonds's "Ophelias." The image of torticollis on page 113 merits high rating for preservation, contrast and composition but it is not as interesting, aesthetically, as the two images on the opposite page, and none of them have the medical importance or aesthetic force of Jennie's picture. A closer ten for medicine on the Gretchen scale would be the image of osteitis deformans on page 131 although points would have to be taken off for lack of visual contrast and expression. The terata on pages 204 and 197 appear to be in great condition, are aesthetically interesting and they get high marks for their Hirst medical provenance, higher than the monster on page 201. The image of Osler has incredibly high rating for its medical significance, but aesthetically its an "eh", although if we were able to see the cadaver warts on Osler's hands the score might go up. Dercum's photograph on page 193 would have a high score, especially for its medical significance, except that both image and science is derivative of what was precedent at Salpetriere. The photograph of fingernails on page 70 rates very high aesthetically, but its weak medical content brings down the score. The Highley King Stone daguerreotype is as close to a ten as anything I have seen. When the Gretchen scale is applied to old masters, a painting like the Anatomy lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp becomes prominent and clarification comes to why we especially value a Van Gogh (it is a study in mental illness) or a Venus de Milo (the tension of apotemnophilia and apotemnophobia, erotitization of the stump).

38.) Griffith, J. P. Crozer, (1885), The area of the murmur of mitral stenosis. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co.;

"The American Journal of the Medical Sciences"; vol. cx., pages 271-281.

39.) Bernays, Augustus Charles, (1885), An operation for the relief of impermeable occlusion of the œsophagus of

five years' standing, with dilatation by a new method. St. Louis: C. B. Woodward Co.; pages 3-8.

40.) Bernays, Theka, (1912), Augustus Charles Bernays: A Memoir. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Company; page 161.

41.) Kemp, Martin, (1997), "A perfect and faithful record": mind and body in medical photography before 1900.

London and New Haven: Yale University Press; "Beauty of Another Order." pages 120-149.