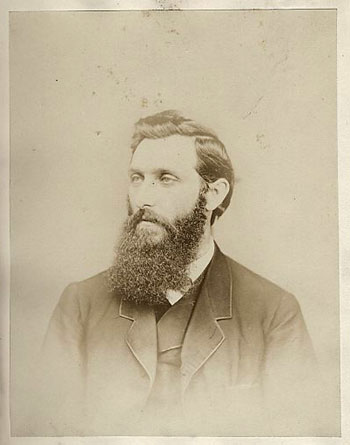

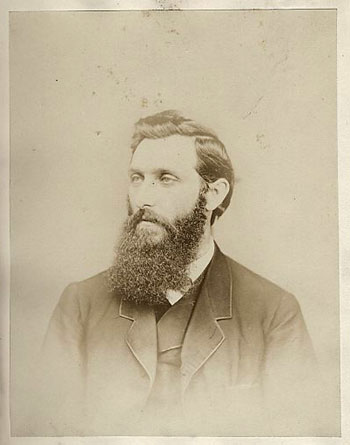

(BILIOUS SANGUINE)

their laws in relation to marriage and the fatal consequences of their violation to progeny, with the indications of vigorous life and longevity; followed by a fugitive essay on the protection of society against crime, by...

Cincinnati : Keckeler, 1869 [2nd ed.] ; cincinnati : H. W. Derby, 1856 [1st ed.].

Description : (2) l. port., [i-ii], i-viii, 246 pp. ; ill., (2) port. front., 23 cm.

Photograph: mounted albumen portrait of the editor, A. T. Keckeler.

Subject: phrenology.

Cited: Cordasco 60-1446.

Note:

The photograph of Keckeler is captioned, "BILIOUS SANGUINE".

Only the second posthumous edition has the albumen portrait of the editor and publisher, A. T. Keckeler, who also contributed some very brief prefatory notes. The brothers Keckeler wrote the following:

The Editors being, by the will of Professor Powell, placed in possession of his unpublished manuscripts and his phrenological cabinet of crania, and illustrations—having been delegated by him as his successors, after a most thorough course of his personal instruction, with his Diploma of "competency to teach and practice the Science," will, as far as may be consistent with other duties, endeavor to fill his place as teachers to those who may desire a more extended instruction than the necessarily limited illustrations of this work can offer.

The cabinet of crania cited by the Keckelers was Powell's collection of over 500 skulls, second in importance only to the collection of the more learned Dr. Samuel G. Morton, father of American physical anthropology.

An introduction of twenty-five pages in small font is given to a public dispute that the more eminent Charles Caldwell prosecuted against Powell within the pages of the newly established American Phrenological Journal. As a protege of Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, the German physician who introduced Americans to phrenology, and as a Philadelphia doctor who had studied under John Bell at the University of Pennsylvania, Caldwell distinguished himself from the many peripatetic "head readers" who debased the science. Caldwell attacked Powell for making claims that he could examine a human skull and ascertain the subject's ethnicity, complexion, color of hair and eyes, and even the subject's religious faith. With a letter to the editor of the Journal, Powell responded that a phrenologist is required to gather facts for his science and that in order to do this he must be a peripatetic "head reader" no differently than a geologist is a peripatetic "mineral reader" or an ornithologist is a peripatetic "bird reader." Powell has a point. Phrenology originated with the eighteenth century writings of Franz Joseph Gall who speculated that the brain is a congeries of organs with separate functions. This was a radical theory for which the gathering facts was made with calipers and other rather crude measuring devices. The occasional head wound would offer a rare opportunity of direct observation and there is a wonderful passage in a biography of the phrenologist Charles Combe (Charles Gibbon, The Life of Charles Combe, MacMillan : 1878) which describes Combe's examination of the daughter of James Mapes, a New York City lawyer residing at 461 Broadway. His daughter fell from a window at the age of 4 and lost a portion of her skull without sustaining any injury to the brain. Combe writes:

The part of the skull removed was that which covers the organs of Self-esteem and Love of Approbation. She does not wear any plate over the wound, but the hair over it, like that on the other parts of the head is fine, and is kept short. Immediately after the wound was closed her father was struck with the variety of movements in the brain, and its great mobility during mental excitement, producing, as he said,a sensation in the hand when placed on the integuments, as if one were feeling, through a silk handkerchief, the motions of a confined leech. He felt as if there was a drawing together, swelling out, and a vermicular kind of motion in the brain; and this motion was felt in one place and became imperceptible in another, according as different impressions were made on the child's mind; but not being minutely acquainted with phrenology, he could not describe either the feelings or the precise localities in which the movements occurred. He observed also, that when the child's intellectual faculties were exerted, the brain under the wound was drawn inwards.*

Combe continues with an analysis of the child's character appertaining to the phrenologic regions exposed by the wound and although we now know his conclusions were wrong, this is one of the first direct observations in the difficult science of regional brain function. By the 1850's Phrenology debased into a popular science in spite of the efforts of Caldwell, John Bell, Combe and others and books like Powell's proliferated. Powell even took to marriage counseling, soliciting daguerrotypes from prospective couples for a reading of their compatibility. There is a chapter on marriage in the book as well as chapters on crime and, his specialty, a supposed measurement of vitality. However the greater portion of the book is given to the usual woodcut illustrations of famous personalities with commentary on the bumps of their heads. Powell is particularly flattering of Dr. Edward H. Dixon, publisher of The New York Scalpel and includes a long biography extracted from the Phrenological Journal.

It is rare to find a phrenological text illustrated by photography. By the time photos began to appear in medical books, phrenology had debased into a popular science and it is easier to fudge the facts with an artist's line drawing. The image of Keckeler which represents the "bilious sanguine" type could easily represent any of the other types in the book.

*For the rest of this passage and more information on phrenology I highly recommend Dr. John van Wyhe's site, The History of Phrenology on the Web, which provides links to numerous txt and rtf files of historical texts.