Upsala : sans publisher, sans date [1864].

Description : [1] p., 15 pl. ; ill.: 15 photo. ; obl., 27 cm. x 36.

Photographs : 15 large mounted albumens on decorated boards.

Photographer : Emma Schenson (1837-1913).

Cited :

Soulsby, Basil Harrington, A catalogue of the works of Linnaeus ; London:

British Museum, 1933 (2nd edition), page 175, Soulsby 2733 :

"Only about 20 copies were circulated. This copy is from the library of Maxwell

Tylden Masters [1833-1907] and inserted is a specimen of Lonicera Ipegena,

accompanied by the following note by Dr. Masters : Lonicera Ipegena gathered

in the Botanic Garden, Leyden, April 15, 1877ůfrom a tree planted by Linnaeus,

&c. With an authograph letter from Dr. Lars Aksel Anderson [1851-1923],

Íverbibliotekarie, Kungliga Universatetet, Upsala, to B.B. Woodward, May 2, 1908,

at which date this work was not in any Swedish Library, an omission since rectified."

Note :

Soulsby's estimation of edition size may be

overcompensated. Several typographical errors in the text indicate that this work may have

been a proof edition done on speculation and only a handful produced, perhaps

as few as 10. Furthermore, there is no bibliographical description of the work

in Tullberg, except for a footnote to the description of the Bystrom marble

(Tullberg 363) which cites a Schenson carte-de-visite of the statue.

No copies are listed in OCLC. The Victoria & Albert only has a broken set

of about 6 of the plates.

The following laudari a viro laudato was written by Goethe in a letter to his friend Carl Friedrich Zelter on November 7, 1816 :

Dieser Tage habe ich wieder LinnÚ gelesen und bin Řber diesen au▀erordentlichen Mann erschrocken. Ich habe unendlich viel von ihm gelernt, nur nicht Botanik. Au▀er Shakespeare und Spinoza wŘ▀te ich nicht, da▀ irgend ein Abgeschiedener eine solche Wirkung auf mich getan.

[Today I have been reading LinnÚ again and am quite unnerved by this extraordinary man. I have learned an infinite amount from him, not just in botany. Outside of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know of no one who has had such a wrenching effect on me.]

No less a man of stature, Elias Magnus Fries also paid many tributes to Linnaeus during his lifetime and used his position as head of the botany department at Upsala Universitet to promote Linnaean systematics and to commemorate his predecessor. Today Fries is remembered as the "Linnaeus of mycology" and he is preeminent among the honored "Patron Plant Scientists" whose names are cut into the limestone facade of the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens Administration Building.

Fries was born in Femsj÷ of Smňlandia, a small province in southern Sweden, where his father served as pastor to a small parish and where he was instructed in Latin by his father from an early age. It is said that he spoke Latin fluently before he learned his mother-tongue, a skill he used to great advantage in his research of the ancient herbal texts. In 1834 Fries began teaching at Upsala and in 1839 and again in 1853 he was appointed Rector Magnificus of the University, a position that is rotated among tenured faculty members. By this date, he was published widely and his reputation was unsurpassed in the field of cryptogama, with the identification of over two hundred species attached to his name. Isley remarks that Fries was "... a child prodigy who yet in his teens probably knew more about the fleshy fungi than anyone in the world except Persoon" (D. Isley One Hundred and One Botanists 1994 ).

Although Fries was LinnÚ's greatest champion at the time, much of his advocacy was in the form of lectures and unpublished letters. This portfolio provides a visible representation of the work he did in preserving the memory of Linnaeus, a life work that was continued by his son Thore Magnus Fries (1832-1913) who published in 1903 what remains today the best biography of Linnaeus (Th. M. Fries, LinnÚ: Lefnadsteckning, I-II ; Stockholm, 1903).

It is a mystery why this portfolio was never published in a wider edition or why, if it was meant to be a commemorative, the text is not in Swedish or the descendents of Linnaeus did not own a copy, most notably Tycho Tullberg (1842-1920) who omitted the portfolio from his exhaustive compilation of the portraits of his great great grandfather which even included small woodcut images of Linnaeus in obscure science journals. The Fries portfolio is an extraordinary lacuna in the Tullberg work. The typographical errors are perhaps an indication that this is a printer's proof edition, perhaps issued as a prospectus for a larger work. If there was an English patron who sponsored this portfolio, it probably would have been someone associated with the prestigious Linnaean Society of London, perhaps the daughter of the naturalist Thomas Brightwell who published a popular biography of Linnaeus in 1858 and which was reissued in 1863 (C. L. Brightwell, A life of Linnaeus ; 1858, 2nd ed. 1863). Thomas Brightwell was an amateur microscopist who discovered a species of Notommata and he would have had a reason to correspond with Fries who is credited for introducing microscopic techniques into Linnaean systematics. Even if Brightwell's daughter Cecilia did not directly sponsor this portfolio, certainly her biographies excited an interest in Linnaeus and made a compelling case for sponsorship.

It is also very likely that Thore Magnus Fries had a hand in creating this portfolio. Thore succeeded his father as prefector of the botanical gardens at Upsala University who retired from that position in 1863, the year when this portfolio was conceived. It is about this time that father and son began petitioning the Swedish government to acquire the estate of Hammarby where LinnÚ spent his summers and which was still owned by his descendents. When the purchase was finally made in 1879, Thore Fries was honored for his work and named Hammarby's first director. Unfortunately, his father passed away the previous year and was not present to share in the glory.

Could the portfolio have been intended to shame the Swedish Government into providing the resources to preserve the last vestiges of LinnÚ's legacy? It must have been a sore point among the Swedish illuminati that their greatest scientific treasure, LinnÚ's personal library of 3000 books, herbaria and manuscripts were acquired by a 24 year old Englishman, Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828), for a small sum of 1000 guineas and carted off to London in 1784. Smith was made a fellow of the Royal Society for this coup. In Upsala, which Linnaeus transformed into the cynosure of european scientific research, very little was done to preserve his legacy until the purchase of Hammarby. The portfolio would have also served as a token of gratitude that could be given to potential donors. The copy in the repository of the Linnaean Society of London (established by Smith and its first president) was donated by Oscar Dickson, Sweden's greatest philanthropist of the nineteenth century. A transplant from Scotland who built a timber and shipping empire in Gothenburg, Dickson was made a Baron by Oscar II in recognition of his philanthropy which funded a number of great scientific expeditions, most notably those of Adolf Eric Nordenski÷ld which included two polar explorations. Thore M. Fries accompanied Nordenski÷ld on his expeditions from which he penned several important works including, Svenska polar-expeditionen ňr 1868 med kronoňngfartyget Sofia (Stockholm : P.A. Norstedt, 1869.) and a treatise on a branch of botany in which he had a world acclaimed expertise, On the lichens collected during the English polar expedition of 1875-76. (Linn.soc.Lond. Jour. Bot. v.17, p.346-370, 1879). The question that presents itself here is : if this portfolio was used to solicit funds from Oscar Dickson, were they funds for Nordenski÷ld's travels or for the purchase of Hammarby?

The circumstances which led to the creation of this portfolio may never be completely known and much of the commentary here is speculative, but without a doubt it is a marvelous visual representation of the importance of Linnaean science in the mid nineteenth century.

Photographer :

The photographer Emma Schenson was considered the foremost photographer in Sweden during this time period. Her training as an artist is apparent in the retouching she applies to several of the images in the portfolio. Unfortunately, all of her negatives, including the ones for these plates, disappeared after death and are probably destroyed.

The following descriptions for Plates 9, 12, and 15 are transcribed from the online catalog to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London :

[Plate 9] In 1864 the Swedish photographer Emma Schenson made a series of photographs in memory of the Swedish botanist Carl von LinnÚ (1707-1778), who was known as Linnaeus. Most photographs in the series are taken in his house (now a museum) in Hammarby near Upsala, Sweden. Linnaeus furnished his home as a kind of personal museum. Almost every detail of the arrangement has a close relationship to his work. In the bedroom the walls were papered with proof copies of drawings by Charles Plumier (French botanist, 1646-1704) and Georg Ehret (botanical artist,1707-1770). The curtain on the bed is printed with a decoration based on his favourite flower, the Linnaea borealis.

[Plate 12] This photograph was taken at the home of botanist Carl von LinnÚ (known as Linnaeus) at Hammarby near Upsala, Sweden. Linnaeus devised the first consistent binomial classification system for plants, which is still used, in a modified form, today.

Schenson's practice as a painter (as well as a photographer) is evident here. She used a painting by Johan Henrik Scheffel (dated 1755, and still in Hammarby) as part of a lively composition. She placed objects of the botanist's daily life, such as his hat, teacup, teapot, and tea caddy, with the painting. His walking stick leans against a chair, as if its owner might return at any moment. Schenson also indicates Linnaeus' place in an ancestral portrait gallery, positioning Scheffel's painting so that the sitter's head appears in line with the two female portraits (his wife and his mother, perhaps) on the wall in the background.

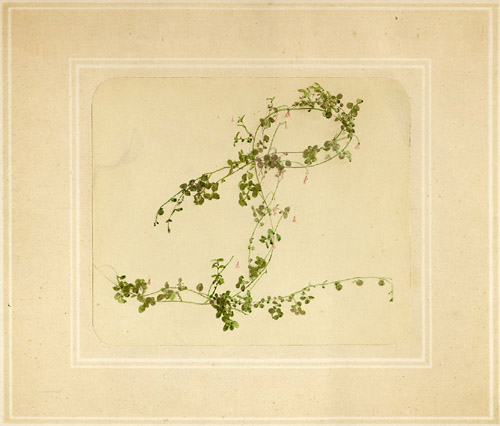

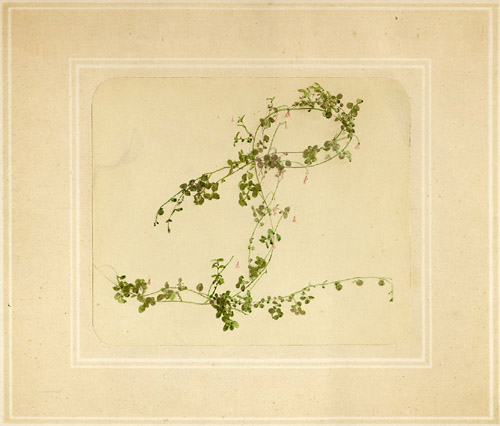

[Plate 15] The hand-coloured photograph shows the initial of the famous Swedish botanist Carl von LinnÚ (1707-78), who called himself Linnaeus. The letter 'L' is created by the Linnaea borealis (twinflower), the flower of Linnaeus' coat of arms.

Linnaeus introduced the consistent use of binomial terms for both plants and animals. In this system of classification every name has two parts, the first for the genus and the second for the species. Linnaeus added his initial 'L' after the names of plants that he was the first to describe. Thus the initial created by Linnaeus' favourite flower epitomises his work.