Chard : ca 1865-1930.

Description : approximately 410 half-plate glass negatives ; 3 framed photographs.

Subject : Orthopedics — Prostheses and surgical appliances.

Repository : Science Museum London.

Cited :

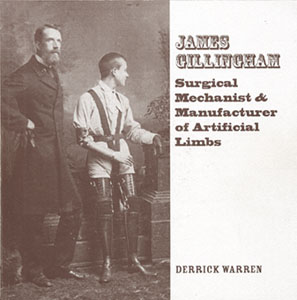

Warren, Derrick, James Gillingham, surgical mechanist & manufacturer of artificial limbs ;

Somerset: Somerset Industrial Archeologocial Society, 2001.

Notes :

The following are object numbers and descriptions from the Science Museum Catalog :

1979-192 : Glass plate negatives (10"x8"), 7, showing portraits of people with

artificial legs fitted by Gillinghams of Chard, Somerset, late 19th to early

20th centuries.

1979-191 : Half-plate glass negatives, ca.400 (some broken), showing artificial limbs,

taken by Gillinghams of Chard, Somerset. ca.1890-1930.

1979-190 : Framed photographs (2) showing patients supplied with artificial aids by

Gillinghams of Chard, Somerset, 1903.

1979-189 : Framed photograph of man in invalid tricycle, by Gillinghams of Chard,

Somerset, early 20th century (?)

For a modest fee, the Science and Society Picture Library offers photographic reproductions printed from about 40 of the negatives in the Gillingham collection.

Surgical Mechanist & Manufacturer of Artificial Limbs.

Important works sometimes lapse unremarked by reviewers for the book trade and unnoticed by readers and bibliographers. The following brief essay is a review of Derrick Warren's biography on James Gillingham which was published by the Somerset Industrial Archeological Society in 2001 (ISBN number 0-9533539-5-8). So far as I know, this is the first review of the book, made obscure perhaps, because it is categorized as a history for a localized industry in Great Britain. However, I argue that Mr. Warren's work should be considered vital for a reappraisal of Gillingham's contribution to the narrative of photography and is a must-read for art historians. Copies are hard to come by in the United States, but the books are available for purchase directly from the publisher. Inquiries should be made through the SIAS website »».

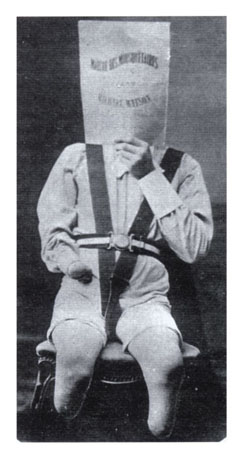

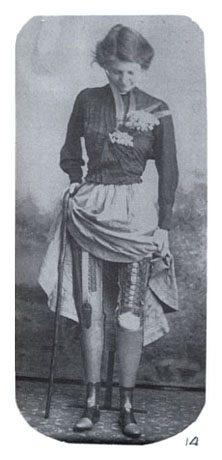

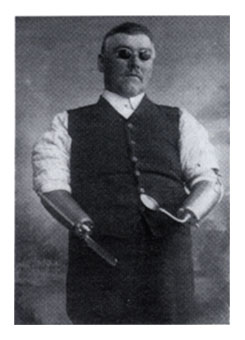

Photographs of amputees who model beautifully sculpted artificial limbs illustrate nearly every page of Derrick Warren's biography on James Gillingham, the genius Gepetto of prosthetic devices. They are images that Gillingham took in a studio he built for this purpose behind his house, but today JG is honored less for his accomplishments as a photographer than he is for the successful surgical appliance manufactory he built out of a small boot and leather goods business he inherited from his parents. The bootery served the citzens of Chard England, and except for a brief stay in London in 1863, Gillingham lived his entire life in Chard. His prosperity was ensured when in 1862 the Taunton branch of the Western Railway connected Chard to London and other commercial hubs of England. In most cases it was only a day's journey for clients to reach the Gillingham shops.

Warren draws from a wide range of historical records for this biography, including patent applications, newspaper accounts, medical journals, JG's published works and a few documents which escaped destruction when the Gillingham works was liquidated in the 1960's. The company documents were preserved by the Chard Museum and included many photographs of patients but only a few family photographs. Another archive of 400 large glass plate negatives survived the liquidation and are now preserved at the Science Museum London which sells prints of the images through its online Picture Library »».

Gillingham was a prolific photographer and the treasurable images that survive may represent only a fraction of the photographs he took over a lifetime. The earliest photograph in the book is probably an image of a leather spinal truss and hip splint that he fabricated for a local physician soon after his return from London and it provides evidence that JG was already a skilled photographer at the age of 25. He got his first commercial success two years later from a prosthesis he made for William Singleton, a local gamekeeper who lost his arm when a cannon he was tamping discharged prematurely. The photographs JG took of Singleton won the endorsement of several leading London doctors including Paget and Sir William Fergusson, extraordinary surgeon to the Queen, who encouraged him to publish an engraving of his device in the January 19, 1866 Lancet. Shortly thereafter JG received another client, a double amputee whose prospect for artificial legs was considered hopeless by London surgeons. The prostheses that Gillingham invented for this young man were again celebrated in The Lancet :

The 'Leather Leg' is prepared by a process known only to the inventor; it is strong, light, and durable, easy wearing and not likely to get out of repair; simple in construction, and as beautiful as life in appearance. It does not take a fortnight to make, but if necessary can be completed in four days. The 'Leather Leg' cannot boast of being applicable to patients at a distance, but the patient must be on the spot, to have the limb properly fitted and adapted to his individual case. All cases are not alike: some stumps are too short, others too long; muscles shrunk to the bone, open ends, bad flaps, stiff jounts, disease in the stump, and many other difficulties known only to the practical limb fitter, which renders any fixed rule in making a leg or arm impossible.

By the year 1910, Gillingham had treated over 15,000 patients, assiduously documenting many of them in his studio. More than seventy of these clinical portraits illustrate Warren's monograph and include multiple views of a few of the patients. The author also provides period photographs of orthopedic devices and inventions as well as views of the Gillingham works and portraits of family members. Gillingham was an entrepreneurial photographer, reproducing the images as wood engravings in medical journals and his commercial pamphlets and broadsides. More importantly, however, he used the photographs to instruct surgeons on amputation technique that best preserves the functionality of a limb. JG's devotion to his clients was always unambiguous, evidenced by the living accomodations he provided for his clients in his home during the time of mensuration and fabrication of a limb.

There is however, an ambiguity of desire in the composition of his clinical photography which compares with Bellmer poupées, or with a contemporary cinematic erotomachia such as Edward Scissorhands. In his best images Gillingham arranges the model before a canvas landscape which, given his protean talents, I have no doubt he himself painted. These are the same erotically charged preparations that an artist makes with a model when he arranges drape and limb to suggest a nudity that is transfigurative. Likewise, Gillingham proposes that an artificial limb can entirely replace a real one and that a damaged beauty, even sexual beauty, can be reconstituted through the power of the artistic imagination. It is a modernist conceit that prosthetic beauty can substitute for idealized beauty, but Gillingham would have cringed at this kind of schematic recollection of his work. Here in the Cabinet, art and medicine are construed ambiguously, thereby providing space for works like the Gillingham masterpieces that evoke the perdurable mysteries of the human condition.