Photograph 79 exhibits a complex expression of joy mingled with grief. A mother has just lost one of her children. Another is attacked by the same malady. She watches anxiously each symptom, and, discerning a salutary crisis, exclaims: " He is saved !" Hide the left eye of the face (79), and only joy appears, but the contraction of the left eyebrow under the rheophores expresses a painful reminiscence mingled with it. To exhibit this play of contrasted emotions, mask the right eye and look at the left side of the face. In order to complete this expression, tears must flow, but this is not within the power of electricity.

Between these primordial expressions of joy and of grief there is no absolute antagonism, provided they be moderate. Thus we have the melancholy smile, a lightning of contentment, which cannot dissipate the traces of a recent grief or of habitual vexation. Homer has invented an analogous situation in the adieus of Hector and Andromache, when she receives into her arms from him their babe Astyanax, smiling through her tears (δακρυοεν γελασασα).

In Photograph 80 we behold the expression of compassion grafted upon the fundamental expression of joy, by electrifying the lesser zygomatic muscle.

Suppose the young woman represented as visiting a poor family. Upon the left side of the face we see only the smile of benevolence; but, if we conceal this, so as to confine our attention to the right side, upon which the rheophores act, we see this smile modified, as by compassion. By localizing electrization upon the lesser zygomatic (the muscle of weeping), the furrow between the nose and lip deepens its concavity, while the upper lip is slightly raised upon a line with the point of attachment of the lesser zygomatic below. It is difficult to maintain the contraction long enough at the proper, degree to be photographed, or so as to avoid grimace.

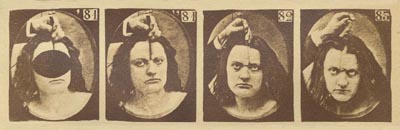

Photographs 81, 82, and 83, represent the expressions of aggressive malignity, by the electric contractions of the pyramidalis nasi.

In the young person whose face has just now assumed the gentlest expressions of tenderness, the development of the pyramidal muscle is so full that its isolated contraction under the rheophores gives a dramatic play of cruel instincts, which her will has no power to evoke and which are latent in her character. The same phenomenon was observed in a great number of subjects. May we not infer that the aggressive muscle of malignity is one of those which least obey the will, and that, most frequently, it is put in action only by the instinct or mode of passion of which it is the essential agent of expression?

It is remarked that the muscle of benevolence (fascicle of the orbicular fibres, which contract the lower eyelid) is equally rebellious to the will, and obeys only that gentle movement of the soul which renders the look sympathetic, as upon the left half of Fig. 80. Herein is a foresight of Nature, forbidding us easily to dissemble or to mimic those expressive lines by which man can distinguish his friends from his enemies. Let us consider the same face in the character of Lady Macbeth; Fig. 81 may portray her in the scene where she exclaims---

"Had he not resembled My father as he slept, I had done't."

Here is a moderate contraction of the pyramidal, which

does not yet give to the countenance that terrible aspect

which it will presently assume. But, under a tender

reminiscence, this heart is still of bronze, as we perceive

by the hard look and threatening attitude. She

would be queen, even at the price of her king's blood!

Maternal love, no more than filial love, can exclude

cruelty. Lady Macbeth loved her babes as the shewolf

loves her cubs.

In Fig. 82 a stronger contraction of the pyramidal seams her brow with cruelty and invokes the fiends of murder---

" Come, you spirits That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full Of direst cruelty! Make thick my blood, Stop up the access and passage to remorse; That no compunctious visitings of Nature Shake my fell purpose."