Edited by J. Nelson Borland, physician [and] David W. Cheever, surgeon.

Boston : Little Brown and Co., 1870.

Description : 688pp. ; illus., 9 plates (1 col.), 26cm.

Photography : 2 leaves with mounted albumens.

Subject : clinical reports, cases, statistics.

Note:

The Countway Library describes a copy with 3 mounted photographs.

These are statistical reports for 6,585 patients treated in the first five years of the Boston City Hospital which opened its doors in 1864. The hospital treated an additional 19,000 out-patients during this time and by 1868 it was already evident that Boston needed another 500 bed facility to care for the health of its burgeoning population.

Article III, pages 108-155 is titled Cases of Pneumonia and was written by Dr. Borland.

Article VI, pages 235-273 is titled Treatment of Skin Diseases and was written by Dr. Howard F. Damon. He includes a case of Leucopathia affecting the left side face of an 11 year old girl who was also somewhat lame in the left side of her body. Also of interest are the three lithographs which illustrate the Article. One of these, titled Lichen Syphiliticus Annulatus, is an image copied from a photograph which reappears as Plate XVI in Damon's atlas of dermata titled Photographs of skin diseases (Boston : James Campbell, 1870).

Five of the fourteen Articles were written by Dr. Cheever who was chief of surgery at Boston City. Dr. Cheever graduated from Harvard in 1858 and remained a Harvard man throughout his life, in 1893 becoming a Professor Emeritus at the medical school. Cheever edited the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in 1868 and was a regular contributor to the journal, but is probably best remembered for his autopsy report and the forensic testimony which he presented as a government witness at the Lizzie Borden murder trial in 1893.

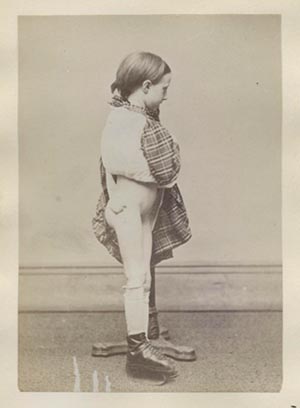

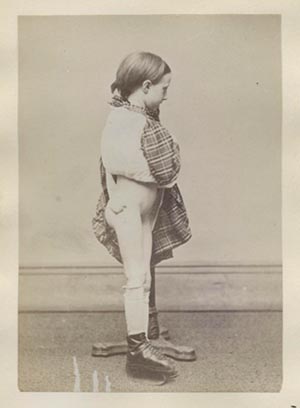

The most compelling of the Cheever Articles is number II (pages 71-107) titled Excision of Joints, illustrated by two albumen photographs and a lithographed drawing of a father holding his daughter whose elbow was excised. The photos are haunting images of a girl named Martha S. whose coxalgia led to an operation to remove the head and neck of her femur.

It is possible that Martha was infected by her mother who died of phthisis, an approximate and antique medical term for consumptive lung diseases, pulmonary tuberculosis in particular. It is equally possible that this poor girl was infected by drinking milk tainted with the bacterium Myco. bovis which was the source of most skeletal TB until decades later when pasteurization and testing was legislated. A total of 11 cases of hip disease are reported, nine children and two young adults who underwent the operation of excision with death providing the outcome in two of the cases. Most of the patients were first treated by extension and weights which was the Rx of choice for wealthier patients who could afford a year or more of quality nursing in the home. Boston City was chartered to serve Boston's poor, however, and for the less disadvantaged patient, aggressive surgery was the preferred treatment for carious joints. Cheever supports his methods in the following two passages:

For poor children, if treated by palliative means, as rest and extension, in

the hospital, who must be sent back, sooner or later, to the wretched

surroundings where they contracted the disease, and from which they were

taken, going back with the disease not removed, a relapse is certain and

aggravated: whereas, by excising the diseased head of the femur, we do away

with the seat of the trouble, and give a better chance for recovery.

To sum up for a moment:

1st. Hip-disease is far from always fatal.

2d. It is amenable to palliative treatment, if begun early.

3d. Excision, then, among the better classes of patients, should be practised

sparingly, and as a last resort. But,

4th Among hospital cases a different rule applies; and excision should be

resorted to as soon as caries is certain, in order to give the patient a

quicker recovery, and a surer drainage when he leaves the hospital. And,

5th. The operation itself, as an operation, will be much more successful if

done early in the disease.

An agressive surgeon, Cheever contrasts his modus operandi against that of his colleague and friend Oliver Wendell Holmes who preferred to operate only as a last resort. He leaves it to the reader to draw parallels between the mortality table of Holmes (6 deaths out of 19 operations) with that of French physicians ( 85.71 % mortality) who were also reluctant to excise a diseased bone.