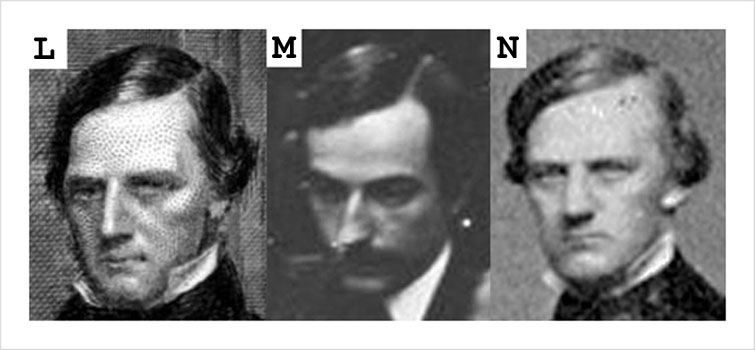

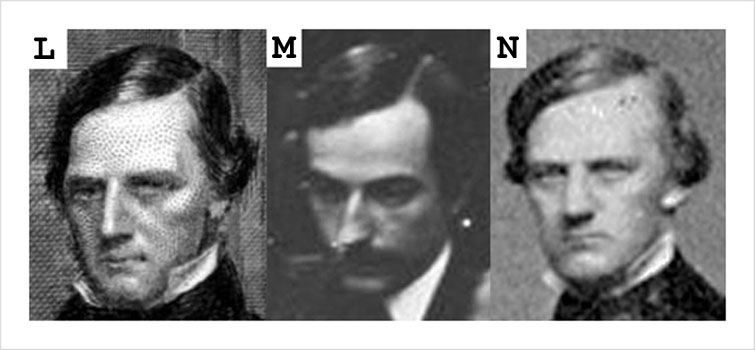

Views of Samuel Parkman: L.) Detail from Henry Bryan Hall's engraving, age c37. M.) Parkman, age 30, detail of Figure 7 in EDD No. 1. N.) Parkman, age c37, detail from the 'Boston Society for Medical Improvement' photograph, c1853. Archived at the Countway Library, Boston, and accessed through Wikipedia »».

Returning to the portraits in Hall's engraving, it can be seen that Samuel Parkman's visage and the contours of his body are an almost perfect match for Figure 7, after adjusting for the shift in perspective and the fact that it is the etherizer's hand on the operating chair, not his. Having established that Hall had access to the so called "reenactment" daguerreotype, proven by the flipped profiles of J. Mason Warren and Bigelow, why then is Parkman's portrayal not also flipped by the printing process of the engraving? The answer has two parts. The first part is that Hall's model for Parkman was copied from the 'Boston Society for Medical Improvement' group photograph taken in 1853. The second part is that Hall's portrait of Parkman proves the existence of an original daguerreotype of the group photograph. Hall modeled Parkman from the original daguerreotype, and not from the low resolution, washed-out, flipped paper copy that is displayed in the panel above.(48) In the paper print, Parkman has aged seven years and appears to have taken on weight, his brow is furrowed and he seems to be scowling at the camera, distorting the brow line and narrowing the palpebral fissures – expressing the "surly reserve" referenced by Darwin in my introduction. His dorsum nasi appears much fuller than it was in reality and his lantern jaw has been softened by the weight gain. Because Hall had access to the pristine details of the original daguerreotype of the Medical Improvement Society, these distortions don't appear in his portrait of Parkman and it is an unqualified match for Figure 7, evinced by the prominent chin (prognathism), aquiline nose, prominent cheek bones, and somewhat puffy lower eyelids – all distinctive features that are almost invisible in the paper print.

The Medical Improvement Society photograph is discussed further in Appendix 1 below. Until the original daquerreotype is found, Hall's engraving should be the resource for identifying Figure 7 as Parkman, though doing so shreds the reenactment scenario that claims it is Bigelow. The table below should help to settle the dispute:

|

PARKMAN:

|

BIGELOW:

|

Samuel Parkman was never called to testify in the Morton patent trials, so chances are diminished that he assisted in the Abbott surgery. He is rarely more than a footnote in ether historiography. The Richard Manning Hodges monograph on the history of ether included Parkman's two humerus reductions prosecuted with ether, and four surgeries without, found in the appendix, "Operations at the Massachusetts General Hospital between October 18 and December 31, 1846, inclusive." But within the general text, Dr. Hodges mentions Parkman only once, listed among the other members of the 1846 surgical and medical staffs at MGH, and nothing more. (49 »») Seven of the twenty-six operations recorded in the appendix were conducted with ether and are notable for showing that Parkman was the first Junior Visiting-surgeon to operate with ether, followed by Bigelow's first ether operation for hydrocele and slough of the scrotum. There is no record for J. Mason Warren's operations conducted with ether in 1846 at the hospital. The Hodges appendix is also notable for showing that Morton's name only appears twice subsequent to the Jackson patent suspension — on December 5, as the anesthetist for Dr. Hayward, and on December 12, for Dr. J. Collins Warren.

Out of all the surgeons whose activities predated the inception of ether at MGH, Dr. Parkman had considerable personal experience of ether's physiological effects and could attest to its safety, revealed in a letter written by Morrill Wyman (1812-1903). The letter was addressed to John Collins Warren's grandson and namesake, who included it in his inauguration speech on the history of anesthesia.(50 »»)

|

CAMBRIDGE, February 15, 1897 MY DEAR DR. WARREN: Your note with regard to experiments with ether at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1836 has reached me. I remember well our amusement with sulphuric ether; Dr. Samuel Parkman was the House-surgeon, I was House-physician, and Mr. C. K. Whipple House-apothecary. We were especially jubilant when Mr. Whipple ordered a fresh quantity of ether, for it was apt to deteriorate by keeping. Each tested it by breathing it from the bottle till it produced unconsciousness, the others watching the different effects upon each. We also experimented upon rats in a glass-globe until they were entirely motionless and often wondered that the treatment did them no harm. But with all our experiments we never thought of trying the sensibility under ether, even by pricking with a pin. It was a great oversight. As ever, sincerely yours, Morrill Wyman |

Wyman was appointed House-physician, August 7, 1836, and Parkman was appointed House-surgeon two weeks later. Both participated in the recreational "ether frolics" that livened the parlors of Philadelphia and Boston medical students and young professionals in the 1830's. Arguably, the MGH doctors must have moved quickly to put professional distance between the duties of their primitive anesthesiologists and the licentious behavior of the ether frolickers. Parkman was indeed emboldened by his experiences as a frolicker to introduce ether anesthesia for a minor procedure, thereby demonstrating its near absolute safety. Understandably however, his past experiences were too sensitive, too controversial to be included in the record until Wyman's revelation a half century later when the medical establishment had attained full control of the narrative.

Detail from Hinckley's painting of the Abbott operation. Like Hall and Keller, Hinckley modeled his portrait of Parkman from the "Boston Society for Medical Improvement" photograph. It is a more youthful, painterly interpretation of Parkman that loses the aquilinity in his features. His prominent cheekbones, and chin were softened somewhat, but still visible.

Comparative views of Samuel and George Parkman: O.) Samuel Parkman, detail of Figure 7 in EDD No. 1. P.) Figure 1 (reversed) in EDD No. 1, identified by the artist/author as Charles Bertody, but presented here as a possible attribution for George Parkman. Q.) George Parkman, detail (reversed) from EDD No. 2 – also unverified.

Adding to the confusion of the Ether Dome iconography is the appearance of "fancy waistcoat" figure in EDD No. 2, who I believe is one of the Parkmans, either his uncle George or his father, both physicians who were well connected to Massachusetts General Hospital. Trace evidence to support this claim is found in Keller, who used the body of this figure for his portrait of Samuel Parkman in his painting. Lowry & Lowry identified Morton in the "fancy waistcoat" figure, whereas Haridas purported Bigelow, based on Bigelow's penchant for flamboyant attire. However, George Parkman also wore expensive vests, notably one in purple silk on the day of his murder in 1849. Morton, too, had a taste for flashy haberdashery, described in Slade's memoir and quoted under the Dalton segment below. A prominent protruding jaw was a distinguishing anatomical trait of the Parkman family, and George Parkman was caricatured in the press for it. His chin bone and mandible were destroyed when he was murdered and dismembered by Harvard Professor John Webster in 1849, and it was entered into evidence during the trial. Morton was George Parkman's dentist, but he testified in part for the defense, disavowing that the "mineral teeth" introduced as evidence could be identified as his appliance.

Although trace evidence points to Bertody as Figure 1 in the so called "reenactment" daguerreotype, a secondary consideration for George Parkman will be premised on Jonathan Mason Warren's March 13th surgery, discussed under that segment below. The deep shadows and degradation in the matrix of the daguerreotype prevent establishing either identity with any confidence. Nor is there any certainty to the identity of the "fancy waistcoat" figure in EDD No. 2, whose attire seems out of character within the formal construct of an operating theater – stationed as he is at the head of the patient as though he were a principal, supervising the anesthesia.

Each of the artist depictions discussed above feature Dr. Samuel Parkman as one of the centermost principals of the Abbott surgery, and yet his role is ignored in the ether stories told by historians, his name deprecated from their rosters of the "reenactment" surgeons. This neglect is remarkable considering Parkman's intimacy with the effects of ether. Crucially, he was the first junior Visiting-surgeon to accomplish an ether operation — the sixth historic ether operation at Mass. General Hospital establishing the safety of ether for a minor operation — and his report on the case was published in BMSJ, constituting the third classical paper on anesthesia, preceded by reports written by Bigelow and John Collins Warren for the journal. His December 9th operation treated a case of urgent care reduction for a dislocated shoulder sustained by a "stout carpenter" named William Eckels, who will be discussed below as the most probably identity of the patient in the so-called "reenactment" daguerreotype.

48.) Unknown photographer (c1853): "Oliver Wendell Holmes and members of the Boston Society for Medical Improvement." [Boston]; archived at the Francis A. Countway Library, Picture Collection, Ser. 249, box 3, f. 3. See Appendix 1 for information on the date.

49.) Hodges, RM (1891), "A Narrative of Events Connected with the Introduction of Sulphuric Ether Into Surgical Use."

Boston: Little, Brown, and Company; p. 29. See pages 149 & 148 for the Parkman record on two patients with dislocated shoulder joints in 1846: William Eckels on December 9, "Dr. Parkman's first operation with ether," and Elizabeth Johnson, age 58 on December 22. His four operations conducted without ether included three seton implants and one thumb amputation.

The record for Bigelow's first ether operation also appears on page 149 of the appendix.

50.) Warren, Jr., JC (1897); see page 11 for Wyman's letter.